For Jada Pina ’26, the gen ed classes she’s had to take to complete her bachelor’s degree in Media and Communications have sometimes felt like a burden.

“I was all for it when it applied to something I want to do careerwise,” she says, “but subjects like math, not so much.”

That’s a common refrain among undergraduate students everywhere. Many also find they reap significant benefits from those core classes, as Pina did when an anthropology course sparked her interest in different cultures and religions and made her realize that “understanding how people’s behavior is influenced by the culture and societal norms they grew up around could help me become a better journalist.”

That’s the kind of light-bulb moment that makes a professor’s day. To get more of those, and to continue to be able to answer the question “Why is this relevant?” Johnson & Wales recently took a good hard look at its Core Curriculum.

But first, what is the Core Curriculum? And why does Johnson & Wales, a career-focused institution, require students to fulfill general education requirements at all?

“The core introduces students to the core disciplines of the liberal arts, the arts and sciences, humanities, social sciences, math and science,” explains Dean of the School of Arts & Sciences Michael Fein. “It provides strong supports in oral and written communication and focuses on the interrelationship of all those fields and disciplines through an emphasis on integrative learning.”

The answer to the second question is that the New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE) mandates that a certain number of credits for a college or university be dedicated to general education. In Johnson & Wales’s early years, the gen ed curriculum was largely designed to fill in the gaps for some of the majors. “If you were a business student, you might need to plug in an economics class,” says Fein. As the university evolved, the core was revised to complement every major.

With the last major revamp now more than a decade old, Provost Richard Wiscott, Ph.D. charged a committee of faculty and staff on both campuses to revisit the Core Curriculum. The goal of this deep dive into the core was to give it a stronger sense of relevance and to increase its experiential and active learning components.

The rationale for the core has not changed. For students who enter JWU uncertain of their major, taking core classes can help clarify areas of interest. “When students come to school at 18 or 19 years old, they may have an idea of what they want to study, but they’ve had little exposure to many of the things that you can learn in university,” says Ann Kordas, Ph.D., a history professor and a member of the committee charged with redesigning the core. “Giving them that background and the freedom to explore can help them figure out the pathways they want to go down.”

Core classes can be equally clarifying for students who feel more certain about their academic path. They are an opportunity, says Associate Professor of Chemistry Chris Roy, Ph.D., to say, “‘Why am I doing this? To see if there might be something else that they’re more passionate about or verify how passionate they are about the discipline they’ve picked.”

Sometimes, says Fein, taking core classes can shift a student’s trajectory. “We might have a student who comes to the university with a strong interest in culinary, and they spend time in the lab, and they decide, ‘You know what, I love food, but I really love my food writing class so I’m going to go into food journalism and leverage my interest in blogging and photography.”

Core classes also develop transferable skills. “What we’re talking about is helping to develop analytic and expressive abilities in our graduates — critical thinking and problem solving, scientific and ethical reasoning,” says Fein. “These are skills that are needed and are exceptionally valuable across all fields. They’re also helpful as people transition across fields, because many of our students take somewhat nonlinear paths through their degree and they will definitely end up in a nonlinear career path. If they’re going to inherit an economic landscape that requires that they move not up a career ladder, but across a career lattice, those skills — the ones not trapped in a specific field or professional pathway — are the ones that will allow them to traverse that lattice.”

The world evolves, adds Roy. “Society evolves, people evolve. If we don't have the ability to change with the world, which is what these liberal arts classes give us the foundational knowledge to do, then how do we succeed?”

The humanities are also asking fundamental questions about who we are as human beings and what makes a life meaningful and how we are fulfilled, insists Professor Mark Peres, J.D., who teaches courses on ethics and a class called The Good Life. “Education serves more than simply professional degree purposes. It's about our mental and social development and it’s the humanities and social sciences that really activate all those questions that catalyze our development as human beings.”

Guided Journeys

In redesigning the core, faculty met frequently with students. From those working groups, says Jessica Sherwood, an associate professor of sociology and a member of the redesign committee, they learned that when it comes to choosing core classes, there are two types of student. “One type says, ‘Please let me do my own thing and explore.’ The other says, ‘Help! There’s no roadmap, and it’s too wide open, and I need some guidance.’” To meet the needs of the latter group, the committee came up with a framework of optional Guided Journeys that make visible a thematic strand in the course catalog that might not be readily apparent to a first- or second-year student.

Guided Journeys identify key areas of interest to students — Food Studies, Media, Entertainment & Popular Culture, Global Citizenship and Health, Medicine & Wellness — and suggest a path through the core related to their interests that will also satisfy their gen ed credit requirements.

“You can explore all that the core has to offer, but you can do it in a way that captures an area of interest for you,” explains Fein.

A student majoring in Public Health, for example, might take core classes on global food security, disease and illness in Western art and the economics of pandemics. For a culinary student a suggested path might include courses on food in film and literature, food writing and the politics of food, human security and social justice.

Make it REAL

The Johnson & Wales approach to education has always been richly experiential. Now, that real-world, hands-on focus is being fully integrated into every course, including those in the Core Curriculum. By 2026, all undergraduate face-to-face courses across the university will have at least one active learning component built into them through a JWU initiative known as REAL (Reimagining Experiential and Applied Learning).

“The overarching connective tissue of experiential learning is something we want Johnson & Wales students to experience no matter what course they’re taking,” says Fein. “Whether it’s a course in the core, or whether it’s in their major.”

Assistant Provost for Experiential Education and Industry Relations Sheri Young, Ed.D, who is heading up the REAL rollout, says what she is most excited about is the scalability of this approach. Using the Kolb Learning Cycle model, which leads students through a sequence of experiencing, reflecting, thinking and acting, all JWU faculty can directly connect the content of their course with the career skills or competencies being sought by employers.

An active learning component could be as simple as taking students on a site visit, says Young, or staging debates or embedding simulation tools into class or working with an industry partner for project-based learning. A critical piece, she says, is having students reflect on the experience though essays, journal writing or group discussions and then bringing their insights back to the course content through some kind of tangible output such as a classroom presentation. Including that reflective/thinking step, she says, “leads students to be more invested and makes them more likely to retain and maintain that skill set.”

Howard Slutzky, Ph.D., a psychology professor, has students in his intro psychology class engage in role-playing exercises so they can practice applying psychological theories to real-world scenarios and become better able to handle complex issues. Students in English Professor Terry Novak, Ph.D.’s Rhetoric and Composition II course volunteer at the Better Lives RI food pantry and reflect on their experience in journals and class discussions while also using research on food insecurity to engage in critical thinking about the population served at Better Lives.

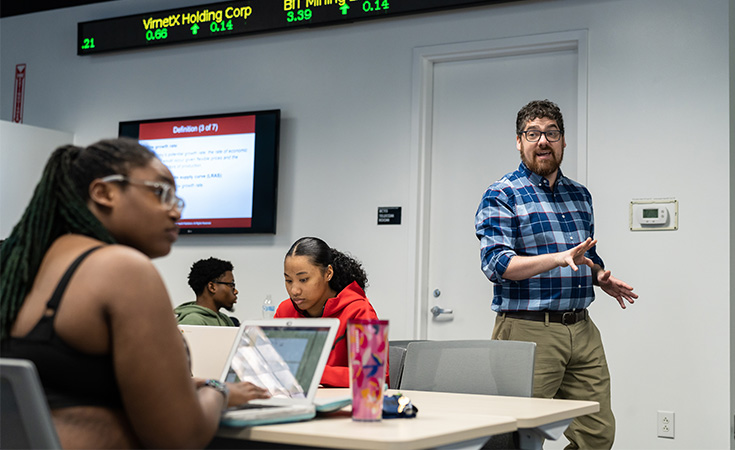

Associate Professor Adam Smith, Ph.D., who infused REAL into his macroeconomics class (see On Course, p. tk), says that including active learning in all his courses has made him a better teacher. “My teaching style used to be lecture heavy. A while ago I realized I could have stood on my head and eaten a pineapple and maybe five students would have gotten excited because that’s not how they learn anymore.” Since he added active learning, he says, the difference in his students’ level of engagement is stunning. “After I’ve done an experiential class, the next class always goes better because they’re still feeling that energy.’”

If we don't have the ability to change with the world, which is what these liberal arts classes give us the foundational knowledge to do, then how do we succeed?Chris Roy, Chemistry Associate Professor

Come on in!

As part of the core redesign, colleges outside of Arts & Sciences can now apply to have their courses included in the gen ed core. As well as adding to the menu of courses a student can take to fulfill their core requirements, this initiative, which is still at an early stage, could help students view their core classes as more relevant to their major.

“If a student from the College of Health & Wellness is taking a course from the College of Health & Wellness that also satisfies a gen ed requirement, they can more readily see how that fits in with their degree in health science or exercise physiology,” says Kordas, who sits on the committee piloting the project.

What’s in a Name?

To help students connect the dots, core courses are now organized (and searchable in the catalog) around attributes — communicating, experiencing, interacting, measuring, exploring and connecting — rather than departments or disciplines such as social sciences, life sciences or math.

“I think these terms resonate better with students,” says Roy, “and also give them a better idea of what they’ll come away with, what sort of transferable skills they’ll learn. The learning objectives are right in the name.”

Persuading students about the value of the core curriculum is part of his obligation as a teacher, says Smith, and something he embraces. “You have to sell it. You have to make it relevant to them. If I have a chef who comes in and they’re unsure whether economics is helpful or not, all I have to do is explain to them why it is. That piece has to be there.”

When Kordas is explaining to a pastry student why the core matters, she’ll talk to them about how sociology courses can teach them about different cultural traditions related to food, while art history courses can refine their understanding of art and design, and history courses can teach them about food and world history. “Those are all applicable to their chosen careers,” she says, “and certainly you need math and science to be a good baker.”

For Sherwood, the sociology professor, the key outcomes of the core curriculum remain her north star. “Because in the end,” she says, that’s what I’m teaching — the thinking, analytics, communication, media literacy. Those are skills that matter, no matter what your major or future profession.”

To give support for scholarships and financial aid, visit below.