Recently, salted caramel was on the agenda in CFIT Senior Instructor Tim Brown’s baking and pastry class.

But instead of following a traditional recipe, his students fed a list of ingredients into an AI recipe generator and prompted it to create a method of prep.

“Cook the sugar,” read one of the steps in the resulting recipe. “What does that mean?” asked Brown, noting that the directions AI spit out in seconds also failed to stipulate that the cream should be heated before being added to the hot sugar. “That can be pretty dangerous if you don’t know what you’re doing,” says Brown, for whom this exercise highlights both the potential and pitfalls of artificial intelligence.

Since ChatGPT’s launch in late 2022, educators everywhere have been grappling with the implications of generative AI technology. Along with the host of other LLMs (large language models) that have since sprung up, ChatGPT can make short work of any number of previously labor-intensive tasks. Type in a prompt and seconds later you’ll have a serviceable line of computer code, a song in the style of Taylor Swift, a term paper, a love poem or a business plan. For time-crunched students, the appeal is clear.

The promise of a shortcut has always been tempting, whether that’s having a friend write a paper, using Wikipedia for research or running an essay through an editing app like Grammarly. AI is hardly new in our lives, either. Any time we use a navigation app or talk to a customer support chatbot or engage with social media we are using AI, whether we know it or not.

What makes generative AI such a powerful game changer for higher ed is its sheer ease of use. Students can now cut and paste assignments directly into an AI tool and produce finished homework with negligible cognitive input.

“It’s just a different world,” says Kristin Pendergast, director of community standards and chair of the academic integrity committee. “For our students, AI is the future. We have to find a way to understand and embrace it and teach students how to use it in ethical, safe and responsible ways, since it’s not going away.”

Assistant Professor Ashley Smalls, Ph.D., who teaches communication skills and rhetoric, agrees. “Our students are joining a workforce that has AI enmeshed in it,” she says, “To try to have them not interact with it at all does them a huge disservice.” Generative AI skills are now part of job listings, adds Senior Instructional Designer Heather Myers. “In order to be competitive, you need to be able to use ChatGPT and DALL-E [a text-to-image model) and have some type of prompt engineering skill.”

Within three months of ChatGPT’s public debut, Johnson & Wales had adjusted its Academic Integrity Policy to address the use of generative AI, and in late 2023, a Generative AI Committee was launched to grapple with issues around teaching, policy, ethics and security. Composed of faculty and staff from around the university, the group continues to meet monthly. “We knew students were using this tool,” says Assistant Professor Diane Santurri, who teaches digital marketing and social media and is one of the faculty members on the committee. “So, it was a real push to get ahead and catch up with them and figure out training and best practices.”

To ramp up faculty’s understanding of AI, the committee hosted several generative AI professional development sessions, and this spring offered a digital badge and a series of workshops through the Center for Teaching and Learning that covered topics such as AI 101, prompt engineering, security and ethics, and how to use AI to design lessons, create grading rubrics and carry out research.

The university’s overarching policy regarding generative AI is that it is not permitted without explicit permission from an instructor, and a student cannot use it in a way an instructor has not specified. Beyond that, JWU faculty have the freedom to use AI in ways that best support the courses they are teaching.

Working with the academic deans, University Provost Richard Wiscott, Ph.D., has charged faculty with three goals related to AI: identifying ways to integrate AI into the new university core curriculum through a course designed to provide students with foundational knowledge on the impact of use of AI in the future; integrating AI into required major classes to help students understand the impact of AI on specific industries they will be working in; and exploring creation of formal AI academic programs and certifications at the undergraduate and/or graduate level, specifically tied to majors such as computer science, cybersecurity and data analytics.

Some faculty have been embracing the technology from the get-go, with caveats. Cybersecurity Assistant Professor Anthony Chavis, for example, “highly encourages” AI use in his classes but requires that students record their prompts and include them in their assignments so he can see their train of thought.

As someone who teaches writing, English Professor Karen Shea, Ph.D., initially struggled with the ubiquity of AI but sees its value in unlocking writer’s block and kickstarting the creative process. The policy she has arrived at is flexible. “If you sit at your computer for a while and still feel stressed or unable to proceed with your writing,” she tells her students, “AI can be helpful, as long as you’re transparent about if and how you use it at any stage of the writing process.”

In JWU classrooms across campus, faculty have been finding innovative ways to engage their students around AI.

Associate Professor Adam Hartman, Ph.D., who teaches math and physics, has his students prompt AI to write code to describe a simple pendulum. He then asks them to identify errors in the code as a way of testing whether they understand the physics.

Students in the Design Department also use AI to write code, this time for website design. Taking away some of the legwork frees them up to focus on user experience, says Design Department Chair and Associate Professor Deana Marzocchi. Students can also get a quick read on a specific demographic by asking AI a question like, “What type of color palette and font would appeal to an audience between the ages of 50 and 70?”

Tasked with developing casual restaurant concepts, students in Associate Professor Michael Makuch’s culinary classes have been using AI to research and analyze demographic trends to decide, for example, whether they should opt for a brick-and-mortar restaurant, a food truck or a ghost kitchen.

For an experiential class making a podcast for the Providence Tourist Board, Bryan Lavin, an associate professor in the College of Hospitality Management, showed his students how they could use AI to analyze the podcast and create 45-second social media clips, making a laborious task manageable while preserving their creative input.

Myers co-designed an online influencer marketing course where students used AI to practice their interviewing skills. After receiving a prompt, the AI tool acted like an influencer responding to a job posting. The students went through an interview process with the AI and then downloaded the conversation into a Word doc to submit as their assignment.

Communications professor Smalls has also used generative AI to make her class more interactive. After downloading her lesson content into ChatGPT she created a simulation game in which her students are tasked with running a workforce and have to decide what communication methods to use at each step. Throughout the game, ChatGPT tests their knowledge of concepts they have learned in class.

Madison McCrea ’26, a business administration major, says using AI is always a process of trial and error. “It never gets it right the first time. It’s more like the third or the fourth and after I’ve been more specific with the prompt or just straight up told it, ‘This is not what I wanted. Redo it.’”

Anthony Chavis, who uses AI widely in his classes for threat modeling and forecasting, starts each semester telling his cybersecurity students, “It’s just a tool. It’s not perfect. It makes mistakes. You need to double check, sometimes triple check, your work.”

For one assignment, he asks his students to create a project management plan using ChatGPT and then to complete the same task by hand. The point, he says, is to show them what AI still lacks. “ChatGPT can give you a good skeleton,” he says, “but you still need the muscles and the tendons and the blood vessels. You’ve got to put all that in there.”

As well as being prone to misinformation, AI is plagued with bias. In one of the GenAI committee’s workshops, participants were asked to identify the bias in a series of AI-generated images. The tool had been asked, “What does a professor look like?” Its answer: white, male, mid-40s, glasses.

While JWU junior McCrea says she and her fellow classmates use AI to help brainstorm and come up with ideas, “we then develop our own opinion and put our own spin on the project.” That individual viewpoint, which AI lacks, will always be powerful, insists Pendergast. “These tools are pretty voiceless, so we want our students to still understand the writing process, to work through and develop their own voice, their own opinions.”

And as much as we anthropomorphize it, AI is not sentient. Its limitations are clear if you’re coming up with new flavor combinations, for example, says Chef Makuch, because it cannot experience taste. Part of his role, he says, is to make sure his students “really sit with the information they’re getting from AI and see if it makes sense. The basics and fundamentals don’t change and our students’ understanding of cooking is more important now than ever.”

One of the less discussed downsides of AI is its impact on the environment. Olivia Loubriel '28, an exercise and sports science major, thinks many people are simply not aware of the energy resources AI’s data centers consume and the greenhouse gases they emit. “My generation is constantly talking about trying to help the environment,” she says. “We’re using paper straws, but on the other hand, if you’re ChatGPTing your homework, how is that helping?”

As well as nurturing their students’ critical thinking skills in a world transformed by AI, faculty are also heeding the call to adapt their teaching methods. “If AI can do the assignment,” says Myers, “maybe the assignment needs to change.”

Because they have such a strong hands-on component, classes in the culinary and health and wellness areas already lean into experiential learning more than written research papers. And academic disciplines such as graphic design continue to emphasize the individual creative process, with students required to produce sketches and mood boards and work through multiple iterations in person during studio time so the faculty can see their designs developing.

For students in business and the humanities, the idea of coming to class to absorb information delivered in a lecture is fast disappearing, says hospitality professor Lavin. “If the lecture wasn’t already dead, it’s on its way out because students can easily use ChatGPT to synthesize a chapter into digestible notes.”

To make the most of class time, he uses a workshop-based approach where students get the information they need outside of class and then meet as a group to learn how to apply and use it in their future careers. “That’s where JWU is uniquely positioned,” he says, “because our faculty have been out in industry and walked the walk.”

AI holds great potential to create customized learning experiences says James Griffin, Ed.D., a professor in the Food and Beverage Department. With input from a student on how they like to learn, AI tools could “customize to their learning style and pace,” he says. In that scenario, the instructor would provide “that vital layer of human experience and wisdom and emotion that contextualizes and makes human the AI enhanced learning.”

Economics Professor Qingbin Wang, Ph.D., urges his students to adopt a mindset of continuous learning and build up their critical thinking and problem-solving skills to bolster their value in this new AI-inflected landscape. “Some people’s job will be more affected by the new technology than others,” he says, “but if you are prepared for the situation, I would say there’s no need to be pessimistic or to panic.”

With every round of industrial revolution—the steam engine, motor cars, computers and now AI—says Wang, people initially worried about losing their jobs. “What we actually found was that each new breakthrough in technology created new jobs, new industries and new product areas. Each time, we actually saw job creation outweigh job destruction.”

AI tools continue to evolve at a dizzying speed—China’s DeepSeek is just one recent addition to the mix—and the technology is unlikely to slow down anytime soon.

“The amount that has happened with AI is extraordinary, and it’s changing all the time,” says English Professor Karen Shea. “Even if you get a handle on it, it’s not going to be the same six months, a year from now.”

Chatting With the Bot

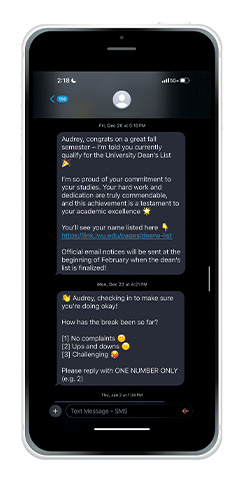

Once a week, Chatbot Willie, an AI-powered texting tool, reaches out to undergraduate students at Johnson & Wales and asks them how they are feeling in four key areas: academic engagement, financial distress, wellness and engagement.

Based on their response, the chatbot can quickly send out links to referral resources or, if the student says something that indicates they are struggling, will send an alert to a team of staff members ready to take action and follow up in person.

“The benefit of the tool,” says Assistant Provost for Student Achievement Dameian Slocum ’00, ’21 Ed.D., “is that it enables us to reach very broadly across the student body, ask meaningful questions, get feedback and then respond in a very timely manner.”

The chatbot keeps a knowledge base of JWU resources and a history of its interactions with students, explains Communications Specialist Derek Lavoie, “so it’s able to synthesize information, keep relationships straight and have meaningful connections with students.”

With a 96% opt-in rate across the university and a 64% engagement rate, Chatbot Willie is clearly filling a need. “Students want to be heard and cared for and responded to, and this doesn’t feel new to them,” says Slocum.

“This is the world they’re most familiar with.” Slocum says he’s been able to share his experience with others on campus. “I tell them we’re already using AI, and students are interacting with it, and we’re okay and they’re okay, so let’s not be afraid of it, and let’s think about how to integrate it in a smart way.”

There’s so much to do (and see) at JWU! Whether you are exploring the Providence or Charlotte campus, you will get an up-close look at what makes JWU great. Explore where you’ll live, learn, and enjoy all campus has to offer.